Women of Montsalvat

History is thick on the ground at Montsalvat, Eltham. The story of the founders of this bohemian artist’s colony are layered into the walls, the very mud bricks they built their gothic looking buildings with. Two families established the colony in 1934: Justus Jörgensen and his wife Lily Jörgensen (nee Smith) and Mervyn Garnham Skipper and Lena Cooper Skipper. It is Justus Jörgensen, however, who is most often described as Montsalvat’s founder and words such as ‘autocratic’ and ‘feudal’ are used to describe the way he ran his art studio. A new exhibition and public art commission intends to reveal the story of the women of Montsalvat hitherto taken for granted.

The arts community in Melbourne in the 1930s was dominated by men and the roles of women highly circumscribed, argues researcher, artist, and the exhibition's co-curator, Amanda Grant. Montsalvat offered an opportunity for women to work alongside men in the construction, design and many other aspects needed to realise a community for artists to live on their terms. Women of Montsalvat begins to reveal who they were and their particular contributions to the creation of not only beautiful buildings, culture and arts practice but the longevity of the project.

Eleven women are the focus of the project so far, which will eventually result in a public sculpture after being voted one of six projects green-lit through the Victorian Women’s Public Art Program.

This exhibition is a work in progress, and it only scratches the surface of the complex and layered lives of these women, often revealing the gaps and silences of the archives.

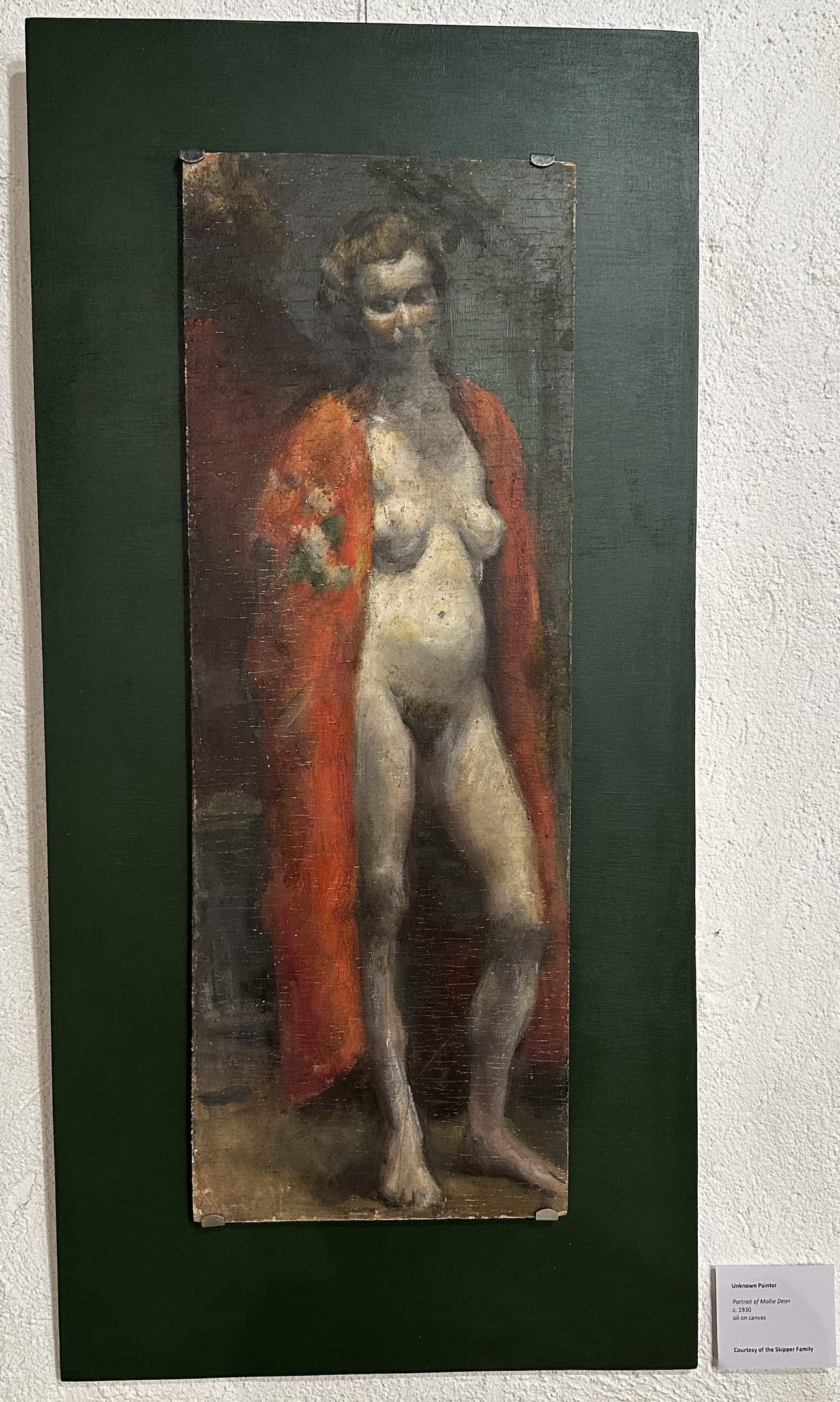

A centerpiece in the exhibition is a recently discovered nude of a young woman named Mary (Mollie) Dean. An aspiring writer who taught children with learning disabilities in an underprivileged school in North Melbourne, Dean was ambitious and her career as a writer was taking off. She had several lovers including Colin Colahan (who was a close friend of Jörgensen) as well as an athlete, and a composer. She moved in elite circles, but Melbourne in the late 1920s could not accept a young woman as ambitious and determined as Dean. At twenty-five, on the threshold of a promising literary career she was brutally murdered in the suburb of Elwood.

The fallout from Dean’s murder could provide clues to the origins of Montsalvat. Dean’s murderer was never brought to justice. Colahan left the country, never to return. Jörgensen never exhibited publicly and four years later was in Eltham constructing a studio away from Melbourne’s glare. Recently her story was the subject of Gideon Haigh’s 2018 book A Scandal in Bohemia.

Jörgensen's wife, Lily Jörgensen (1899-1977) deserves a profile as substantial as her husband’s. As the first woman anesthetist at St Vincent’s Hospital, she supported her artist husband as well as purchased the land on which the first buildings were built. She was a graduate in both science and medicine with an interest in reproductive health and birth control at a time when women’s access to both was entirely prescribed by men. Lily Jörgensen was a polymath who was one of the first translators of psychiatrist Carl Jung’s writing, eventually setting up a psychoanalytic practice at Montsalvat, in spite of suffering from Multiple Sclerosis and paralysis throughout her life.

Lily Jörgensen is represented in the exhibition by a nude portrait by Justus Jörgensen, but there is the strong sense that her story is yet to be told on her own terms. This feeling pervades the exhibition which, as noted, is a work in progress but leans heavily on prior knowledge of the history of Montsalvat. Without Grant's excellent tour I would missed many of the connections linking these key women.

While the exhibition is composed of paintings, drawings, ephemera and jewelry from the Montsalvat archives and collection, the buildings themselves also record female labour. Sonia Skipper (1918-2008) worked with mud brick, mudstone, pisé de terre (rammed earth), limestone and bluestone on many of the community’s buildings, including carving gargoyles alongside Montsalvat woman Helen Lempriere (1914-2000). Skipper served as architect Alistair Knox’s first foreman (foreperson?), and legend has it, says Amanda Grant, taught him the mud brick methods developed at Montsalvat which built many of the 'Eltham style' buildings he is famous for.* In her tour of the exhibition Grant described women and men laboring side by side to build the unique buildings that Montsalvat is now known for. They were equals in these tasks, but they still had to cook, clean, and most likely raise the children themselves.

The cooking, and the food famously consumed on feast days, was made by chef Sue Vanderkelen (1899-1956) who was also a painter, writer, and poet. She was a patron of Montsalvat, and in what becomes a recurring theme in the exhibition, provided essential financial backing. The stone tower linking the first two buildings at the top of the property, known as Sue’s Tower, was made possible by her financial support, among other buildings. She was also responsible for naming the colony Montsalvat (after the castle of the Holy Grail in the medieval tale of Parsifal). Wikipedia would have you believe it was Justus Jörgensen who named the whole thing.

While the Bohemian spirit enlivening Melbourne and inspiring the men and women of Montsalvat to live on their own terms did acknowledge some fluidity of gender roles, it is the women of Montsalvat who come off as far more exceptional than has been acknowledged. Past failures to value their contributions are slowly being repaired and it’s fantastic to see their stories emerge in this exhibition.

The exhibition concluded on 27 July 2025, but keep your eyes out for the public artwork still to come. The Women of Montsalvat instagram page also has regular updates.

~~~

*The State Library Victoria has an extensive collection of Alistair Knox's architectural plans, some are digitised.

Post Script

Slow Looking is written from the perspective of an inland-dwelling critic and historian/art historian, with the semi-regular reviews from capital cities and other locations. You might be curious about other newsletter review projects happening around the country. Here’s a short list of the ones I read regularly. If you know of others - send a link my way.

- Queensland: Lemonade Letters to Art Exhibition reviews and news about art in Queensland written by established and emerging writers, critics, curators, and artists. I thought the title was a reference to life/art giving lemons, and critics making lemonade from them, but it’s actually a reference to the yellow glaze that filters the Queensland sky!

- Western Australia: Dispatch Review Currently their website isn’t clear about how to subscribe, but email them at dispatchreviewxox@protonmail.com and I am sure they can sign you up! Dispatch are an incisive bunch and I’ve learned so much about the art scene in Boorloo/Perth from their work.

- Victoria/New South Wales: Memo Review Melbourne-heavey reviews with regular forays into New South Wales ensure the minutiae of the Naarm art scene is captured in detail. I particularly enjoyed the recent review of the NGV’s French Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts Boston - it summed everything that is wrong with blockbuster exhibitions, or perhaps the approach to such exhibitions catering only to the selfie-weilding art viewer. No slow looking happening there.

All three newsletters are candid and conversational, experimental and never dull; all things that inspire my work on Slow Looking.

Lastly, Blue Art Journal, who also have a newsletter to sign up to, is the name of a new journal dedicated to First Nations art, craft, and design. Soon to be launched by the team behind Art Monthly Australia (which ceased printing recently).

'Blue Art Journal' is committed to elevating global Indigenous ways of knowing and understanding by preferencing multimodal approaches to reading, writing, listening and speaking about Indigenous visual art knowledges. 'Blue Art Journal' aims to transform how critical and experimental Indigenous voices are sustained and engaged across digital and print publishing.

Can't wait to read it!

If this edition looks a little different it's because I have shifted Slow Looking over to Ghost from Substack. Feedback is always welcome, and please share with those you think might appreciate these words.

Happy reading and looking.