Unruly art objects and long-haired hippie types

A series of sculpture exhibitions in Mildura from 1961 to 1988 were a testing ground for new forms of experimental art. A new exhibition at the Mildura Arts Centre documents this moment 50 years on.

The 1970s still feel recent for many folks. For those who remember them it was a vibrant, mad and challenging time. The rest of us live with the complex legacies of this moment. A series of sculpture exhibitions in Mildura from 1961 to 1988 were a testing ground for new forms of experimental art, the impacts of which are still felt in Australian art today even if they have been absorbed into Mildura’s landscape. A new exhibition at the Mildura Arts Centre documents this moment 50 years on.

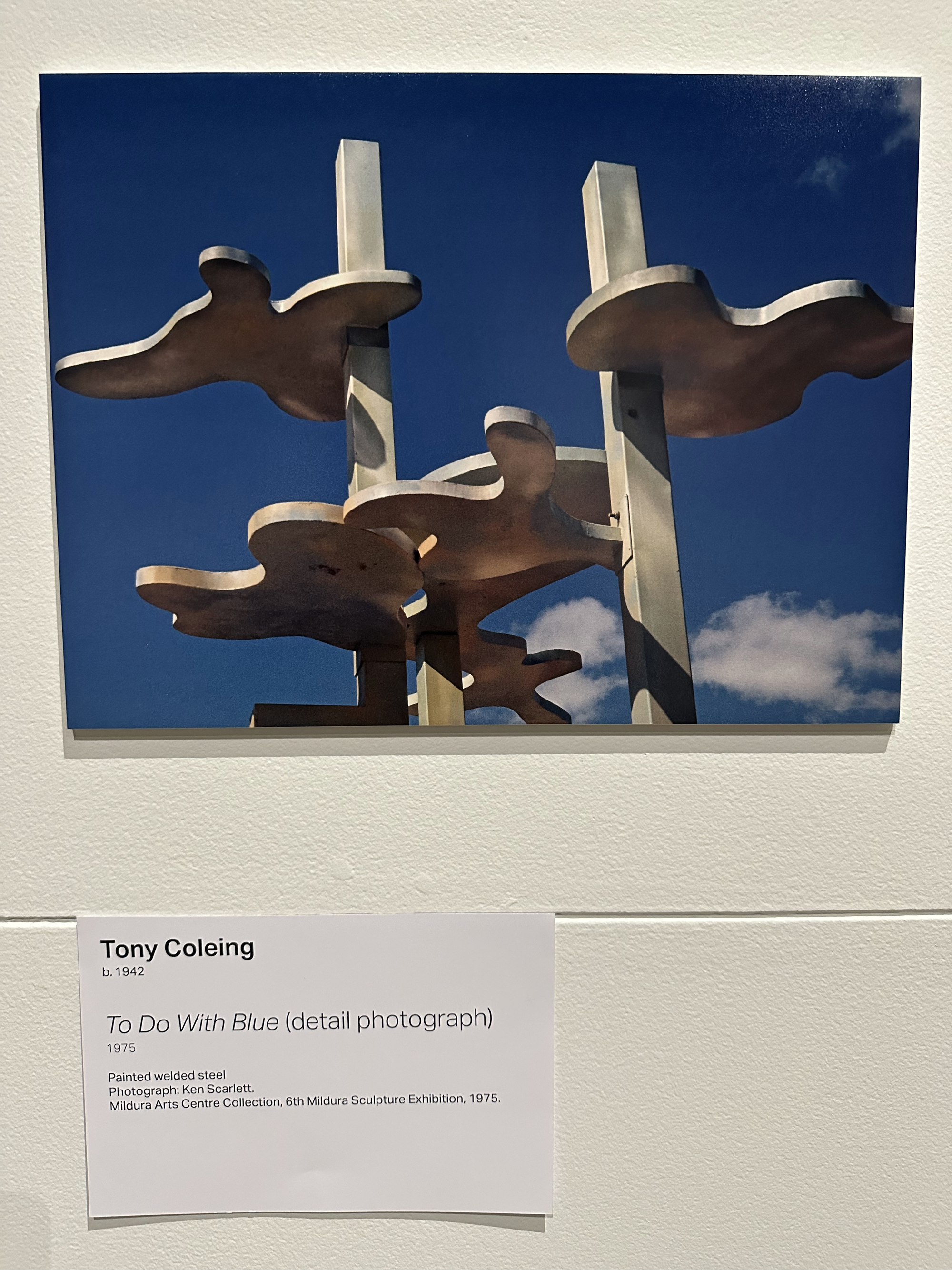

Landmark: 50 Years Since Mildura ’75 uses existing works from its collection as well as newly discovered photographs from the time to recall a moment of experimentation and controversy, the likes of which the regional city probably hasn’t seen since.

Sunraysia residents might be unwittingly familiar with the legacies of the Sculpture Triennials which took place on the lawns around the arts centre and on the former rubbish dump next to the Murray river. It’s easy to drive past some of them without realising: Inge King’s Black Sun sits on Deakin Avenue and was first exhibited in 1975 at what is now regarded as the most significant and groundbreaking of the Triennials. Sculpture nerds, academics and artists with long memories, remember this moment; much like the 70s themselves it was a kaleidoscope of activity that could never be repeated.

This is the impression I get reading its history. Former schoolteacher and Triennial Director Tom McCulloch wove together incongruous ingredients in such a way that new forms of sculpture, performance and what we now call post-modernism flourished in the unlikely desert soil of Sunraysia. Here are some thoughts prompted by a recent visit to Landmark: 50 Years Since Mildura ’75.

Taking art outside the walls of the gallery was extremely novel for the time. Expanding the definition of sculpture to include things like Earth art, conceptual art, performance, and ephemeral installations, similarly set the Sculpture Triennials apart from the rest of the country’s exhibitions. The 6th Sculpture Triennial in 1975 included sculptures made from what were, at the time, highly unconventional materials, including a planted garden on the former rubbish tip below the arts centre as well as less traditional plastics and found objects.

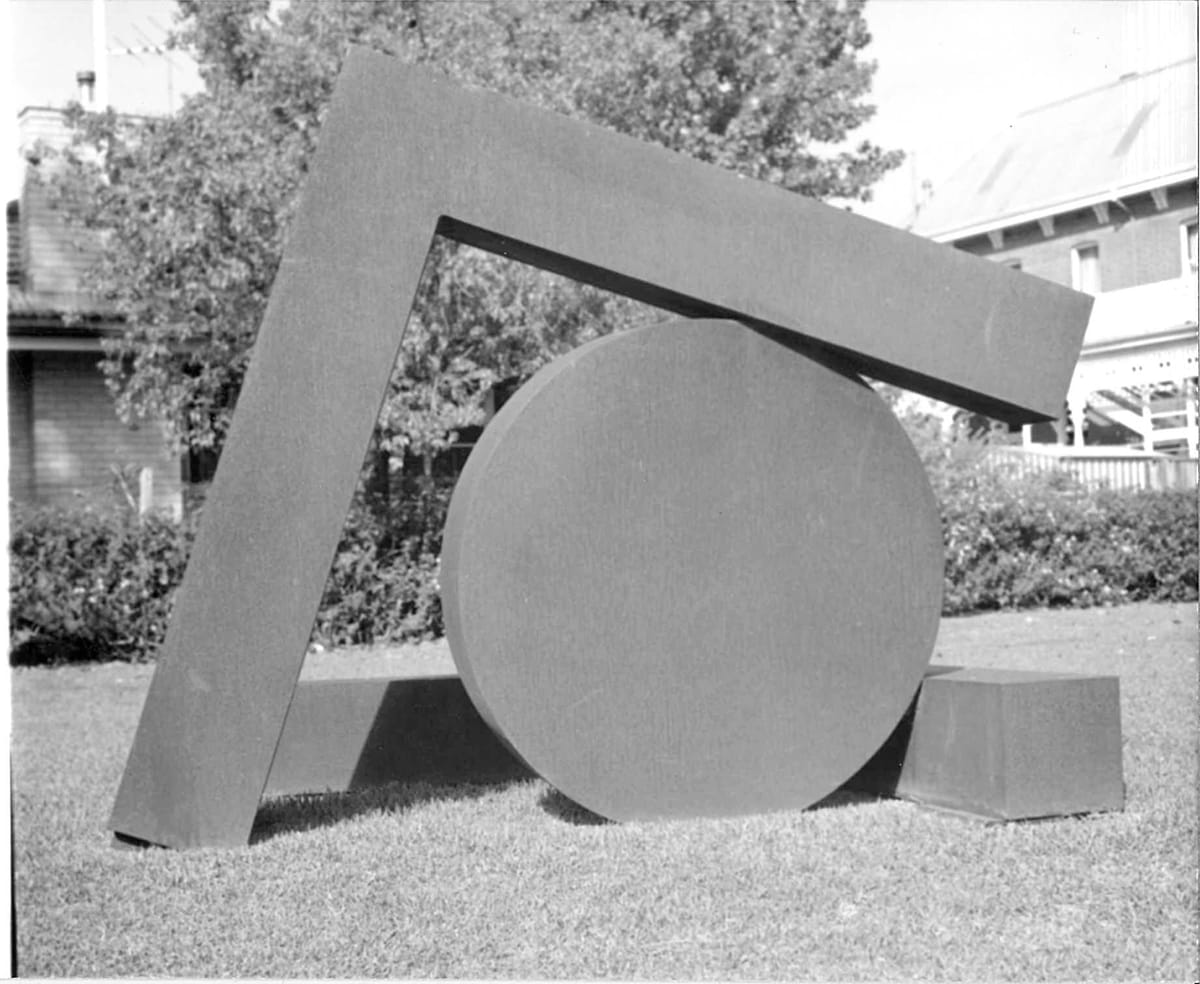

Bronze and steel had been to this point the expected materials used by sculptors, and some sculptors continued to practice this way. Ron Robertson Swann was among a cohort of more traditional sculptors whose works were easily assembled outdoors and did not disintegrate or biodegrade.

Another innovation which led to the Triennials being dubbed the Mildura Model was McCulloch’s collaborative approach which saw artists recommending artists and students travelling from Adelaide, Melbourne, Canberra and Sydney to assist with the artwork installation. McCulloch’s expansive and inclusive approach can be seen in some of the newly discovered photographs by Peter Thurmer which depict the artists (flared jeans, patterned shirts, long hair for the men, and flared jeans, T-shirts, and long or short hair for the women) camping on the sculpture ground.

Performances which took place during the Triennial marked another important development for the artworld and Mildura: the impact of the feminist movement. Thurmer’s photographs projected in the exhibition space are a highlight of the exhibition which does not always meet the challenge of communicating what was new and sometimes controversial about the Sculpturescapes (as they were known) to new audiences unfamiliar with either Sunraysia in the ‘70s or the revolutionary ideas unfolding there for artists and art students from all over the country.

“It was absolutely vibrant, mad, and challenging at the same time. And of course, you start to get the simmering tensions actually becoming evident between some of the more conservative ratepayers and locals and this extraordinary influx of all these fabulous long-haired hippie types from the cities,” according to art historian Anne Sanders during a talk at the arts centre on 13 September.

The tensions erupted in 1978, and the Triennials weren’t the same after that, which makes what happened beforehand all the more important to preserve. Dr Sanders spoke with participants for her PhD dissertation which was completed in 2010. Julie Ewington used this research in a talk given in 2019 at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) which justifies the 1975 exhibition as a defining moment in Australia’s art history. The exhibition features didactics drawing on their words. (I highly recommend the ACCA podcast from Ewington’s speech). It is disappointing to see that more wasn’t made of the opportunity to translate what Sanders’ terms a “febrile period” for contemporary audiences. Fleetwood Mac and other period tunes play in the exhibition space but beyond this it seems like a missed opportunity not to draw parallels between 1975 and 1925. The exhibition would have benefitted from interviews with participants bringing to life their experiences, or even a ‘where are they now’ to showcase the legacies of the 6th Sculpture Triennial. It is taken for granted that audiences will remember Inge King’s Black Sun when next driving through town, but will they remember or know of the Sculpture Triennial that produced it?

In a panel discussion on 13 September Tom McCulloch, now nearly 90, spoke about the challenges of getting experimental art exhibitions off the ground in a difficult political climate. Shortly following his appointment as director of the Mildura Sculpture Triennial McCulloch was invited to direct the second Sydney Biennale, which was effectively the first (to showcase sculpture) of this long running and significant exhibition deploying the Mildura Model. Malcom Fraser’s government after November 1975, and retraction of funding for arts, influenced the vibrant but challenging time for artists and curators. Fraser opened the 1976 Biennale of Sydney, at which artists walked out of the Art Gallery of NSW. McCulloch as director was forced to take a different approach:

“…talking to Mr. Fraser, I find that his conception and interest in art were very sincere. And if you can work with people like that, their politics might get in the way, but you just have to work with them,” he said on 13 September.

I regret not asking McCulloch what advice he would have for artists, curators—and arts workers in general—working within what has become a similarly restricted funding and censorious arts landscape. How should we “work with” those at the top of the pile who have chosen censorship instead of an open mind? The Venice Biennale debacle and the removal and return of Khaled Sabsabi and Michael Dagostino as well as a climate of timidity and fear in which it is possible to apparently instantly de-establish literary journal Meanjin, not to mention the implosion of the Bendigo Writers Festival. Perhaps he would point out that the difference between politicians then and now is the lack of liberal arts degrees among the latter.

The Mildura Sculpture Triennial of 1978 was the denouement of McCulloch’s tenure, a time in which it became impossible to “work with” the newly elected council members who oversaw the Mildura Arts Centre. As the success of 1975 drew more attention, word reached Sunraysia of a performance by Mike Parr, scheduled to exhibit in Mildura, in which he chopped his arm off on stage. The Mildura Council members reading this news didn’t know Parr was one-armed to begin with.

‘Somebody in the [Mildura] council here read the story and said, “oh, my god he’s going to bring bloodletting to Mildura”’, McCulloch recalled at the recent gallery talk.

Alongside “bloodletting”, pornography and nudity were singled out for censorship and in this environment it became impossible for McCulloch to continue as Triennial director.

These nouns refer to a decree issued to [McCulloch] in 1978 by the Mildura Council in relation to the Mildura Sculpture Triennial, i.e, ‘no nudity, obscenity, pornography or bloodletting. It is up to the artists not to cross an indefinable line of public acceptance in Mildura otherwise they could earn the wrath of the community and bring an end to the Triennials’.[1]

McCulloch resigned from MAC in 1978 and shortly afterwards left Mildura. His ability to negotiate stands out in spite of the controversial end to his time here. Securing funding was never easy, regional contexts and communities required careful navigation, and then there were the politics of artists at the time. While it’s hard not to view McCulloch’s 15-year stint in Mildura as an example of radical/experimental/exciting and original ideas being met with backwater mentality; this is too simplistic but not entirely wrong.

One incident brought politics into exhibition planning in a way that seems all too contemporary. A group of artists, lecturers and students in Sydney were part of the anti-nuclear movement, meeting in March 1973 at artist Marr Ground’s house. Donald Brook, Alex Tzannes, Imants Tillers and Tim Burns were scheduled to show work at Mildura in 1973. When French nuclear testing in the Pacific coincided with a proposed exhibition of French sculpture at Mildura (touring to other locations), McCulloch was faced with an artist boycott of that year’s Sculpturescape. He rescheduled the French exhibition to Brisbane after hasty negotiations with the embassy in Canberra and the artists withdrew their proposed boycott.[2]

McCulloch said in a 2010 interview, from his perspective the artists’ actions really only hurt the French sculptors, it didn’t really impact the French government. The French cultural affairs person ‘couldn’t care less’ which cities the exhibition toured.[3] The artists felt the need to act collectively to oppose nuclear testing, and McCulloch either validated their cause, or excused their actions as those of a bunch of hippies, but negotiations and compromise were essential in the face of collective artist action.

Sculpturescape ’73 presented work outside, including earthworks installations and performances and was a key steppingstone towards the defining moment of the 6th Sculpture Triennial in 1975.

Landmark: 50 Years Since Mildura ’75 is worth visiting especially if you lived through the ‘70s and remember them. Younger audiences will be rewarded after some initial background reading, some of which is available in the exhibition.

I recommend Erica Tarquinio's article in Artlink, as well as those already linked throughout. You'll need a library card or institutional log in to read Anne Sanders' article 'Made in Mildura' - but it's on the wall in the gallery. Julie Ewington's talk at ACCA is on soundcloud or podcast apps.

[1] Tom McCulloch ‘Nudity, obscenity, pornography and bloodletting: the impact of Mildura Sculpture Triennials on Australian Contemporary Art, Art Monthly Australia June 2011, 13.

[2] Tom McCulloch ‘Nudity, obscenity, pornography and bloodletting: the impact of Mildura Sculpture Triennials on Australian Contemporary Art, 11.

[3] Interview with Tom McCulloch, 24 March 2010, Deborah Edwards, Art Gallery NSW Archive, 16.