Marking place with Rhae Kendrigan

Another intriguing show at Workspace 3496 +Gallery, a creature to love, and a podcast recommendation.

The traces we leave, and the marks left on us by places we visit, are the central tensions in Rhae Kendrigan’s practice. Their current exhibition is titled Shul to explicitly evoke the marks that remain after the thing that has made them is gone. Kendrigan appropriates this term from Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost, a book that has had a profound effect on the artist. Spending time in different locations across New South Wales and Victoria, these imprints are tied to physical journeys of art making as Kendrigan travels across regional Victoria and New South Wales.

Kendrigan’s methods vary depending on their location. The work in Shul was made at residencies and travels during 2024/25 with the intention of inviting each place, or landscape, into the process which they describe as “a collaboration beyond language with the non-human world.”

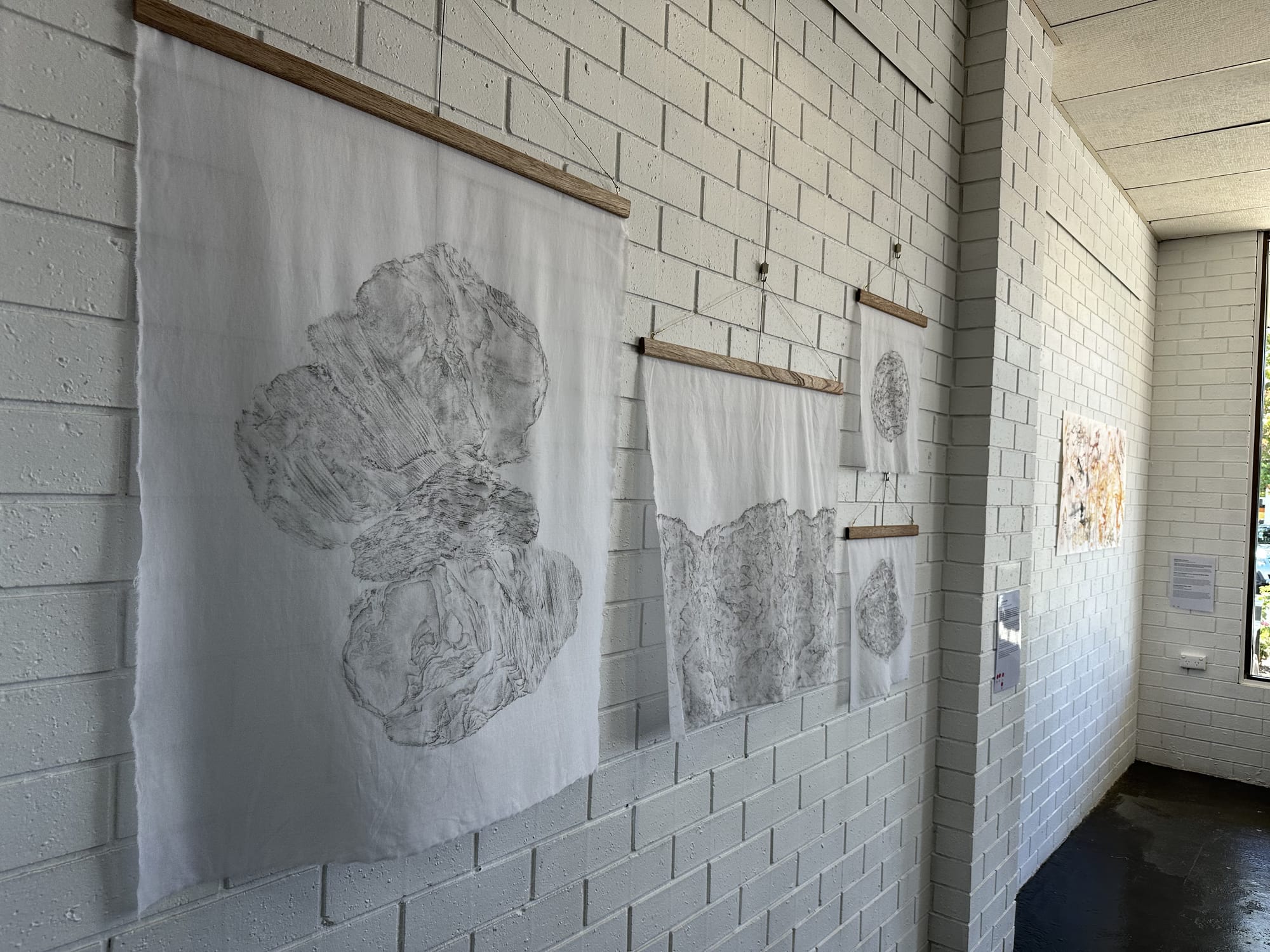

Kendrigan is a performance artist, and this exhibition features the marks resulting from different performances in different media from charcoal to frottage to photography and embroidery. Using a methodology called Body Weather, designed to “develop a conscious relation to the state of change inside and outside the body”, Kendrigan’s approach is often dictated by what they find in each location. This responsiveness is clear in the titular work Shul (2025) in which they drew blindfolded while conjuring the memory of time spent at Bibbaringa Farm in Bowna NSW from the floor of Wagga Wagga Art Gallery. The resulting large-scale scrolls are marked with charcoal and what looks like white chalk or gauche in chaotic and meandering patterns. The types of marks made while standing and wielding a long stick with the chalk attached can only be random and gestural as the performance takes on a durational dynamic.

I enjoyed the gestural quality in When We Burn (2025) the most. Consisting of four smaller horizontal panels of thick paper with charcoal markings, this work has movement and narrative, where Shul seems more of an exploration. When We Burn was a collaboration with ecologist Craig Dunne on Yuin Country in Moruya NSW, an area impacted by the 2019/20 black summer bush fires. The duo dragged the paper through the landscape which had recently been cool burned as part of a fire management program. While none of this is apparent on simply looking, the works do evoke a landscape with their soft and hard black vertical and horizontal lines. The four together tell a story of movement, reminding me of fire.

In Shoals (2025) elements of country make their way onto the page. Ink, clay and salt appear to interact on paper like a chemical reaction forming orange and blue and soft violet bubble blobs on the page. Also made on Yuin Country, this time at Burrill Lake NSW, where Kendrigan spent four days immersed in the waters and surrounding landscape. This series of small works on paper extends the element of chance which is present throughout several pieces in the exhibition. I enjoyed the unusual colour combinations in Shoals but wondered about the ethics of using elements like clay in an artwork that has left its place of creation. Perhaps I am over interpreting the desire to collaborate with the landscape itself, which I don’t doubt is alive. I was left wondering how Country consents to this process.

L-R: Rhae Kendrigan The Holding Place, photographs of performance (2025); Gondwana Coast (graphite on muslin cloth) (2026); Forming a River's Edge (2024) (author's photographs).

In Air (2024) Kendrigan opens themselves up to experiences of landscape shaped by the wind. At the edge of the continent on Bunurong Country, at Point Nepean National Park VIC, they became interested in edges and negative spaces. As part of the Mornington Peninsula Regional Art Gallery’s artist in residence program Kendrigan made a series of monoprints which became the series Air. At once evocative of maps and medical imagining of brains, these works have interesting layers of greys, blacks and whites, which I have come to associate with Kendrigan’s work. The squiggles which dominate the compositions are like the paths of insects across bark.

Kendrigan described their experience at the time: “This place is heavy with story, seeped with history. I can almost feel the weight of that in the earth underneath me. I think that’s why I’m so interested in the edges and the negative space – because it’s the edge between the heaviness of the earth and the lightness of the wind.”1

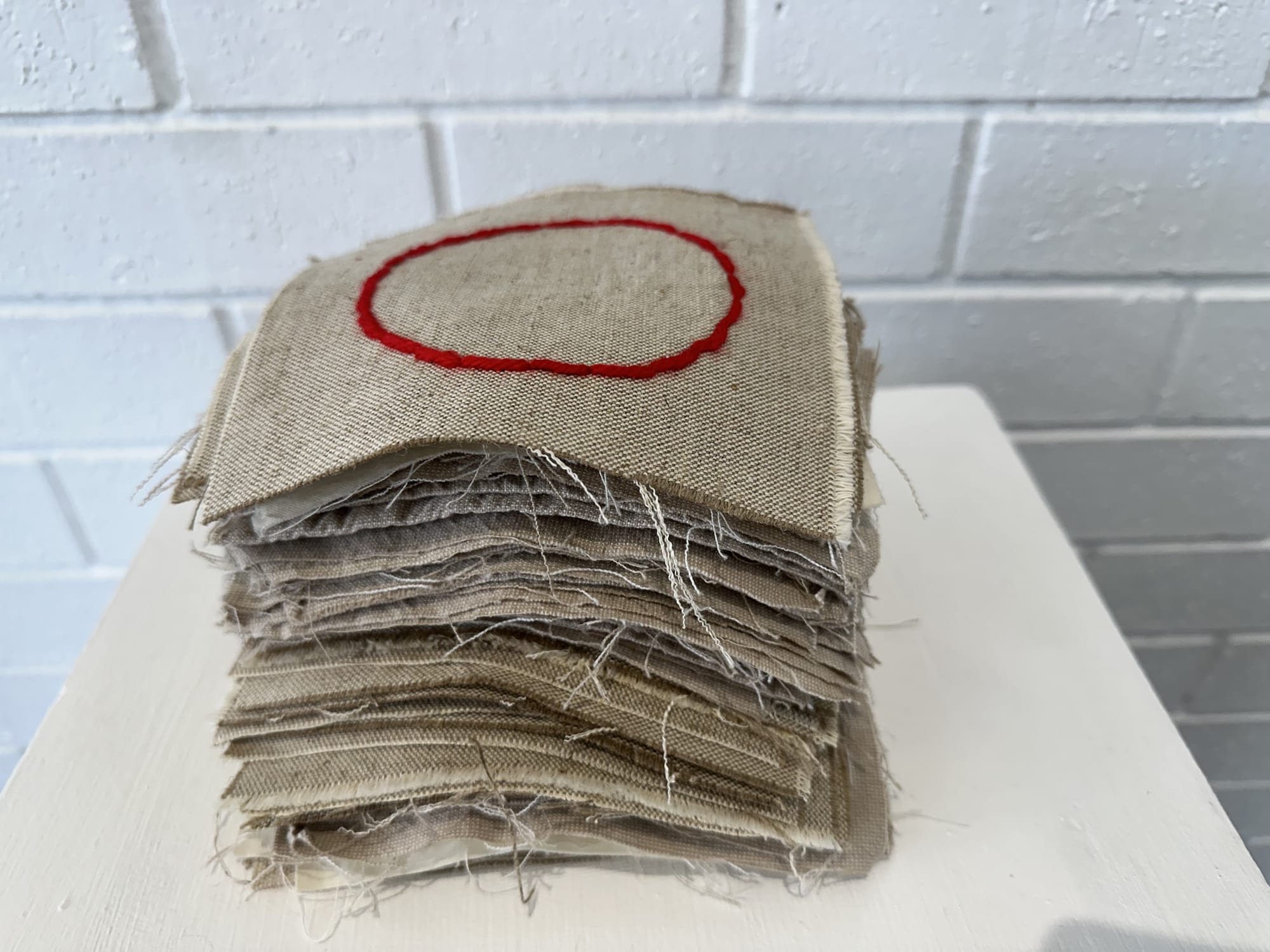

These observations find resonance in The Divine, The Void, The Infinite (108 Circles for Radical Fields), (2024), a durational stitching performance inspired by the Zen practices at Glenlyon’s Radical Fields and Castlemaine Zen (Djarra Country). Using found yarn and fabric, Kendrigan stitched 108 circles in red thread after participating in a Zen walk. The circles are displayed in a stack with their edges fraying, and they seem to wait for the craftsperson’s hands to return. Some circles are framed and displayed on the wall. Symbolism here isn’t derived from the landscape specifically, instead the numbers hold significant meaning to different religions and practices from across the world.

I was most intrigued by the durational element in this work. As someone who performs small repetitive movements with thread and needle (in my case crochet), I appreciated the mental stillness that this creates.

In Gondwana Coast (2026) Kendrigan uses textiles again, this time frottaging muslin on rock formations on Dharawal & Yuin Country at the South Coast of NSW. As these soft pieces of white cloth with stratigraphic markings moved under the gallery’s air-conditioning, there was a sense of two opposing temperaments, the marks left by still and unyielding stone and the porous malleability of muslin. They were a pleasure to watch when I visited the gallery and one of the stand-out artworks.

L-R: Rhae Kendrigan When We Burn (Charcoal on paper) (2025); The Divine, The Void, The Infinite (108 Circles for Radical Fields) (yarn and found fabric) (2024) (author's photographs).

Defined by its intention to be sensitive to place and to build a relationship with the non-human world(s) that we share the planet with Kendrigan’s work takes up important questions aligned with environmentalism as well as First Nations epistemology but does not explicitly step over the territory they’ve delineated for their project. The sovereign Country on which each artwork was made is acknowledged and through the methods mentioned, Kendrigan connects with place in ways that allow non-Indigenous folk to experience a deeper, reflective experience of the world around them. This is all for the good, and necessary. A lack of reflection and comprehension of the ways in which our actions impact those around us, including the more-than-human (as I like to think of them) is what is keeping us in the mess we’re in. [gestures to the world at large]

By way of conclusion, then, the following information about a small but diffident and beautiful creature is not at all out of place. I’ve written before about art, mining, and the impact on this continent’s unique wildlife. Here I draw your attention to the Rakali, one of Australia’s largest rodents and encourage us all to think about how we can act for them in a way that expresses our awareness and sensitivity to place.

Shul is on display until 21 February 2026.

The Rakali is a sweetheart

Don't let first impressions fool you, one of Australia's largest rodents is an intelligent and impressive hunter who plays a critical role in nature. As I recently learned from Banyule Council's newsletter:

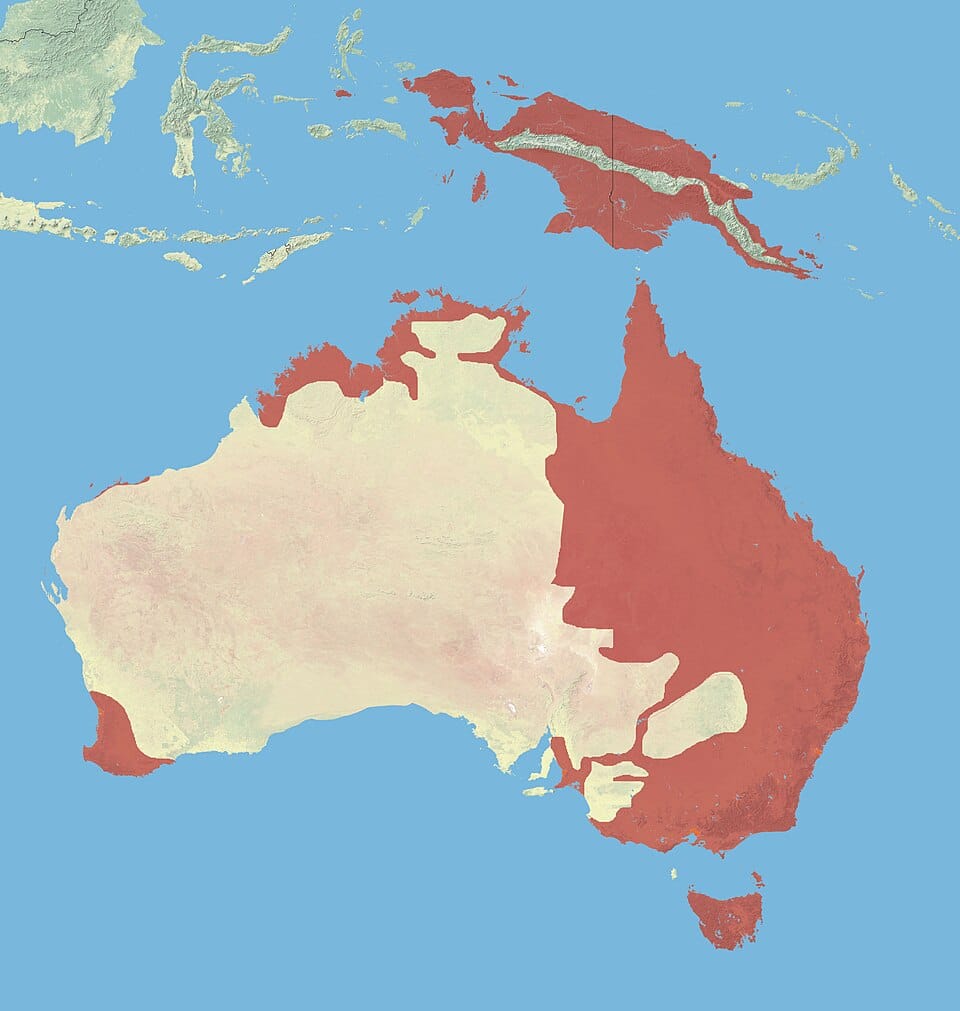

Often called water rats, rakali live along rivers, wetlands, lakes, and coastlines across much of the country. With their dense waterproof fur, webbed feet, and thick white-tipped tail, they’re perfectly adapted for life in the water.

Rakali are skilled hunters. They feed on insects, fish, yabbies, frogs, turtles and even invasive species like carp and cane toads, making them an important part of healthy aquatic ecosystems. Highly intelligent and curious, rakali use their front paws like hands to manipulate food and explore their surroundings.

Despite their adaptability, rakali face serious threats. Habitat loss, polluted waterways, entanglement in fishing gear, and secondary poisoning from rodenticides have caused population declines in many areas. Because rakali are top predators in freshwater systems, their disappearance is a warning sign that waterways are in trouble.

There is something that you can personally do for this little mammal. BirdLife Australia are campaigning at the moment to cease the use of a rodenticides that kill rakali, along with other creatures:

Native birds, wildlife, and even pets are at risk because of the unregulated use of Second-generation Anticoagulant Rodenticide (SGAR) poisons in Australia. These silent killer chemicals are still available on retail shelves and online in Australia, despite the known risks.

These known risks are the unintended deaths of animals through the poison leaching into the wider environment and spreading through waterways and storm water systems:

SGARs persist in animal tissue for longer than many other rodenticides. This means they are more likely to accumulate within an animal to dangerous and even lethal quantities every time a vulnerable animal ingests these poisons.

SGARs don’t kill immediately, so poisoned rats and mice, and non-target animals can spread the danger far beyond where they were exposed to poison. This puts native birds and other animals in the local environment, as well as family pets in neighbouring yards and through our local community at risk.

Wednesday 18 February is Rakali Awareness Day, the perfect time to email Agriculture Minister, Julie Collins, and Assistant Minister, Anthony Chisholm, about why you want to see rakali and all susceptible animals protected from SGARs. The BirdLife Australia website have an easy to send letter form ready to go.

Post script

- If you've messaged me with feedback about the newsletter, thank you! It is heartening to know this project is resonating. If I haven't seen your message it is possible it has gone into the ether, and this is my error - my settings weren't complete for reply emails. They are now, and if you click reply to this newsletter I will now receive your message!

- Lastly, I wanted to recommend this interview with historian Heather Goodall on the History Lab podcast.

Professor Heather Goodall was a pioneering historian whose research transformed understandings of Indigenous history, both in her field and in the broader community. Her work demonstrated a deep personal and professional commitment to social and environmental justice. Heather died peacefully on 29 January 2026, aged 75. In this special episode, we hear her reflecting on her life’s work — more than five decades of historical research, teaching and community engagement.

- Vale Emeritus Professor Heather Goodall - reflecting on a life in history (History Lab 5 Feb 2026) get it wherever you get your pods.

Footnotes:

1 all quotes are from the Shul exhibition catalogue.